I'm back in the station with plenty of time to spare. The agent at the ticket counter has looked after my bags, and what's more, there's no charge ($2.50 a bag at Vancouver station...). It's much quieter now that it was when I got off the 'Canadian'. During that extended stop, the station hummed with excited passengers joining the train, and continuing passengers who were allowed to get off the train to explore the station and get some fresh air. There's a beautiful domed entrance hall in Winnipeg station, but the two ticket desks and passenger lounges are all grouped together in the comparatively cramped and low-ceilinged space beneath the tracks.

20.30hr arrives, and boarding is announced. There are, to be honest, not many people in the lounge. I count maybe half a dozen of us. Unlike the 'Canadian', which is a flagship tourist train, the 'Hudson Bay' is frequently used by locals. Although it's the only form of ground transport to many remote communities north of Thompson, MB, it's also used by passengers going to southern Manitoban towns such as Dauphin and The Pas.

Returning up the escalators I descended earlier, I'm presented with a much more modest sight. Train 693 uses the same carraiges and locomotives as the 'Canadian', but without the elegant dome cars and without the half mile long consist. In fact, our train has just five cars behind two locomotives. There's a baggage car, two coaches, a restaurant ('Annapollis') and a sleeper ('Chateau Levis').

And for a change, I'm heading to the sleeper.

The CanRailPass and North America Rail Pass will give the ticket holder a seat in coach class, and nothing more. If, however, at any stage of a rail pass trip, you feel like a bit more luxury, you can pay the basic accomodation fare and upgrade to a sleepr. In my research I found this train to be significantly cheaper than the Canadian for such an upgrade. Although (unlike the Canadian) food isn't included in the sleeper fare, the cost of an upper berth going northbound and a lower berth returning came to C$247.17 - and that covers four night's accomodation on board the train. I'd heard prices for a single night in similar accomodation on board the Canadian in the region of C$160, so this was a real bargain.

I'm met on the platform by Carmel, the train's service manager, and Tara, the train's chef. Since there's only one sleeper on the train today, and only two passengers in it, she's doubling up as the attendant for this car. She shows a lady passenger the way to her single occupation 'roomette', and then leads me to the other end of the car to my berth (sometimes referred to as a section).

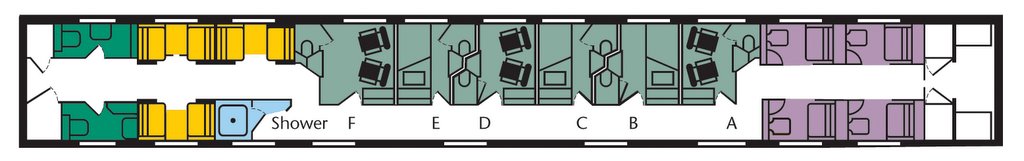

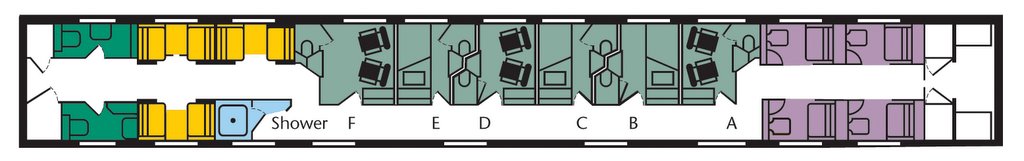

This plan varies slightly from my car, but it gives you an idea. The only other passenger in the car was in one of the purple shaded roomettes. The green shaded bedrooms were unsold, and being used for the crew. The remaining six berths were all for me. I'd booked a cheaper upper berth going north and then a more expensive lower berth going south in order to compare them.

When not converted into beds, these sections appear to be three pairs of wide facing banquette seats. In about five minutes, they can be converted into beds. The seats collapse to form a horizontal surface. A key unlocks the upper bunk, which folds down, and curtains and curtain rails fold out. A nattress for the lower bunk is stored in the upper bunk, and it's brought down to make for a more comfortable bed than just two folded seats. With fresh linen, a duvet and two fluffy pillows each, you have some very cosy accomodations.

With no other passengers for this part of the journey, the process of conversion doesn't have to get in my way: my bed has already been made up and I'm free to sit in the two unconverted pairs of seats. Tara explains everything to me, and gives me a shower amenity kit. Just across the hall from my berth is a shower room, which I look forward to sampling later. Towels, soaps etc are all included. She continues by explaining that, in her opinion, I've made the wisest choice with the berth: the mattress is wider than any of the other accomodations, and she's always slept well in them.

We pull out a few minutes ahead of schedule, and I settle down for a very interesting ride.

We arrive at the small trackside village of Thicket Portage at about 17.30. I've begun to realise that I am hopeless at identifying trees and plants. I'm ashamed to admit that I even had an extensive 'field' education during my A-level general studies class, in which I studied some of England's woodland. Now I am reduced to bad poetry to try and describe the sometimes barren, sometimes straggly scenery of thin woods and empty lakes.

We arrive at the small trackside village of Thicket Portage at about 17.30. I've begun to realise that I am hopeless at identifying trees and plants. I'm ashamed to admit that I even had an extensive 'field' education during my A-level general studies class, in which I studied some of England's woodland. Now I am reduced to bad poetry to try and describe the sometimes barren, sometimes straggly scenery of thin woods and empty lakes.